MAHINA TIARE II’s 1996 CAPE HORN TO ANTARCTICA EXPEDITION

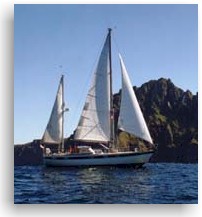

The five-week expedition started in Ushuaia, Argentina, on January 4. From there, it was down to Puerto Williams, Chile, where Mahina Tiare’s crew waited out a cold front that battered the Beagle Channel with 60-knot winds. They then sailed close past Cape Horn and into the infamous Drake Passage. |

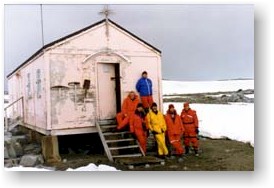

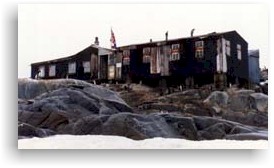

During her visit to Antarctica, Mahina Tiare’s crew met scientists and support personnel at Argentine, British, Ukrainian, American and Chilean research stations. A highlight of the trip was the time spent in Port Lockroy helping five members of the British Antarctic Survey clean and restore an historic hut. It had been built 30 years ago by another British Survey team, but had since been taken over by gentoo penguins and the elements. You really had to be there to appreciate how shoveling out three decades of penguin s__t could actually be considered a highlight of the trip. During her visit to Antarctica, Mahina Tiare’s crew met scientists and support personnel at Argentine, British, Ukrainian, American and Chilean research stations. A highlight of the trip was the time spent in Port Lockroy helping five members of the British Antarctic Survey clean and restore an historic hut. It had been built 30 years ago by another British Survey team, but had since been taken over by gentoo penguins and the elements. You really had to be there to appreciate how shoveling out three decades of penguin s__t could actually be considered a highlight of the trip. The BAS crew subsequently sailed aboard Mahina Tiare to check another isolated hut at Dorian Bay, which Richard Atkinson had built 20 years earlier. They found that structure in excellent shape, and full of supplies from the yacht Pelagic. Gary Jobson, Skip Novak and a small crew were nearby filming segments for an upcoming ESPN special. |

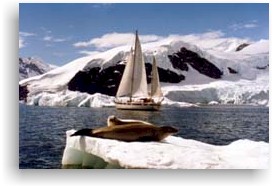

Weather and ice movement presented the most difficult challenges. Several times at anchor the crew had to fend off icebergs with a ‘bergy pole’-a 14-ft carbon fiber windsurfer mast with stainless spikes at the end. And the first time they tried to sail through the Lemaire Channel, they found it totally blocked by huge icebergs driven there by gale-force winds. When venturing ashore, they were surrounded by hundreds of penguins, dive-bombing skuas and breathtaking beauty. At sea and at anchor, they encountered leopard seals, humpback whales and yet more inquisitive penguins.As you might expect, voyaging as far as 65°S latitude was a little different than sailing in most other places in the world. Being summer in the Southern Hemisphere, the air temperature ranged from 20 to 40 degrees. While downright balmy compared to winter, those temperatures and the wind chill made proper clothing essential.Topsides, the uniform of the day was layers of Patagonia and REI clothing. Typical of most of the crew, Al Maher wore lightweight capilene longjohns, followed by an REI expedition-weight polypro layer, a light cotton sweater and a Helly Hanson polypro vest. At night, he’d add a fleece-lined jacket, and when it was wet, Henri Lloyd foulies. Neal favored a Mustang Ocean Class one-piece float-suit – similar to what the Coast Guard helicopter crews use. “But the rest of the crew thought it was too warm and cumbersome,” he says.  Ski goggles were necessary in snow, sleet or high wind conditions. Keeping fingers somewhere between useful and frostbitten proved the major challenge. A three-glove system consisting of Patagonia glove liners, followed by OR (Outdoor Research) modular liner and mitts from REI worked the best.” The engine room clothesline was always full of extra liners hung up to dry,” says Neal. Ski goggles were necessary in snow, sleet or high wind conditions. Keeping fingers somewhere between useful and frostbitten proved the major challenge. A three-glove system consisting of Patagonia glove liners, followed by OR (Outdoor Research) modular liner and mitts from REI worked the best.” The engine room clothesline was always full of extra liners hung up to dry,” says Neal.

The water temperature was so cold that at a couple of stops it froze hard enough to support the weight of penguins that would waddle up to the Hallberg-Rassy 42 for a look-see. The cold water was a big concern for Neal, who reports he was paranoid about catching the dinghy painter in the prop since he didn’t have a drysuit aboard. Then again, the Avon wasn’t in the water any more than it had to be, as leopard seals apparently love to attack and destroy inflatables! A forced-air Volvo Arctic diesel furnace installed two years ago in Auckland kept Mahina Tiare warm below, even in high winds with the boat heeled way over. It was backed up by a heat-exchanger system and propane forced-air furnace, which was rarely used. |

| Mahina Tiare didn’t quite make it to the Antarctic Circle-66°30’S-where it would have been daylight all the time in January. But it was close. Their ‘nighttime’ consisted of four hours of twilight where “You could watch the sunset and rise at the same time,” says Maher.

This meant there was always enough light to check bearings ashore. That was a good thing, as there’s not exactly a glut of cruising guides for the area. Neal used a collection Mooring had its special little nuances, too. Of nine stops, Mahina Tiare only swung on double anchors three times. The rest of the time, she was either tied to shore (usually to rocky outcroppings) with as many as seven lines, or anchored and tied to shore. Neal says the 600 feet of 5/8-inch floating polypro line he got for Chile’s Patagonian coast proved valuable in Antarctica, as well. The bright yellow line was easily visible even when it was snowing, and its flotation properties made it easier to work with when going ashore. The disadvantage: even at two feet, the tides were often enough to ‘float’ the mooring lines off of rocks. As far as site selection for anchoring, one of the prime criterion was finding an inlet whose entrance was shallow enough to keep large bergs out-yet allow Mahina Tiare with her 6-ft draft in. Neal reports that even the big bergs move around a lot and you have to keep an eye on them constantly. “Several timed we encountered huge bergs moving with the current at 2 knots or more – to windward!” he says. At several |

| All Mahina Tiare’s stops save one were on the Antarctic Peninsula, in the island group known as the South Shetlands. Their one stop on the mainland – the actual Antarctic continent – was at Faraday Station, a former British outpost that’s now home to a group of Ukranian researches.

After five weeks in Antarctica (and 17 months in Chile), Mahina Tiare headed for warmer climes. On April 22, she departed Puerto Montt for Juan Fernandez, Easter Island, Pitcairn, the Marquesas and Hawaii. John and Amanda look forward to arriving back in Friday Harbor in early September. Shortly after that, John will be flying to Sweden to check on construction of Mahina Tiare III, a new Frers-designed Hall-berg Rassy 46 which will arrive in Seattle by ship in December.

|

of hand-drawn anchorage charts passed down over the years from several boats. They were an indispensable addition to the British Admiralty and few Chilean charts of the Antarctic Peninsula. These latter were accurate as far as they went, says Maher, “but it’s a little harder to figure out where you are when everything’s white. The hand-me downs tell you, ‘put anchor here, put line there, there’s a spike on this hill’, that sort of thing. They’re excellent.”

of hand-drawn anchorage charts passed down over the years from several boats. They were an indispensable addition to the British Admiralty and few Chilean charts of the Antarctic Peninsula. These latter were accurate as far as they went, says Maher, “but it’s a little harder to figure out where you are when everything’s white. The hand-me downs tell you, ‘put anchor here, put line there, there’s a spike on this hill’, that sort of thing. They’re excellent.” anchorage’s, ‘berg watches’ were posted aboard, and as often as not involved fending off ice with the bergy poles. Three times, the crew used the Avon to push bergs out of the way that were running over the anchor chain or nudging the boat. The weather at the bottom of the world can change rapidly, so accurate forecasts were mandatory for survival. In addition to Bob Rice’s service – which gave accurate forecasts up to five days ahead – the Mahina Tiare crew found the New Zealand ZKLF weatherfax chart (transmitted at 103OUTC on 9459.0) and Chilean charts (transmitted by CBV at 1115, 2315 and 2330 on 4228.0 and 8677.0) to be helpful. Navigation was by GPS – yes, it works fine down that far – and constant dead reckoning updates. Crewman John Graham is a

anchorage’s, ‘berg watches’ were posted aboard, and as often as not involved fending off ice with the bergy poles. Three times, the crew used the Avon to push bergs out of the way that were running over the anchor chain or nudging the boat. The weather at the bottom of the world can change rapidly, so accurate forecasts were mandatory for survival. In addition to Bob Rice’s service – which gave accurate forecasts up to five days ahead – the Mahina Tiare crew found the New Zealand ZKLF weatherfax chart (transmitted at 103OUTC on 9459.0) and Chilean charts (transmitted by CBV at 1115, 2315 and 2330 on 4228.0 and 8677.0) to be helpful. Navigation was by GPS – yes, it works fine down that far – and constant dead reckoning updates. Crewman John Graham is a ship’s captain who loves navigating under the most adverse conditions. When Mahina Tiare left Palmer Station and ended up bottled up and blocked by 90% ice and 40-knot winds in the Lemaire Sraits, John navigated from 1500 until 0300 the next morning, mostly in zero visibility and subfreezing temperatures – all flawlessly, without a single mistake. A Raytheon radar helped this process, showing even small bergy bits as the sea wasn’t too rough.

ship’s captain who loves navigating under the most adverse conditions. When Mahina Tiare left Palmer Station and ended up bottled up and blocked by 90% ice and 40-knot winds in the Lemaire Sraits, John navigated from 1500 until 0300 the next morning, mostly in zero visibility and subfreezing temperatures – all flawlessly, without a single mistake. A Raytheon radar helped this process, showing even small bergy bits as the sea wasn’t too rough.